The Luis Lloréns Torres residential complex was the “perfect project” to analyze, according to architect Nando Micale. “It’s located between these two bodies of water, was built on a mangrove bed, and is the next project to be remodeled by the Housing Authority,” explained the instructor from one of the University of Pennsylvania’s design labs.

The environmental characteristics surrounding the residential complex and the construction policies used to construct it expose its nearly 7,000 residents to increased vulnerability, such as severe flooding and difficulty leaving the complex.

This project, along with other locations in and outside Puerto Rico, was one of the spaces that 35 master’s students at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design used as a practice laboratory to develop suggestions and solutions that would prepare Puerto Ricans and local governments for the effects of another natural disaster, such as that caused by Hurricane Maria.

These proposals were presented at a time when the Puerto Rican government is awaiting approval of mitigation plans required to repeal the nearly $20 billion allocated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) for the reconstruction of infrastructure affected by the hurricane.

Jerry Kirkland Hernández, director of Naguabo’s emergency management program, said he would use some of the solutions presented by the students because “they include angles that hadn’t been considered before.”

Kirkland Hernández was one of four Puerto Rican professionals who traveled from the island to participate as judges in the presentations held on December 18.

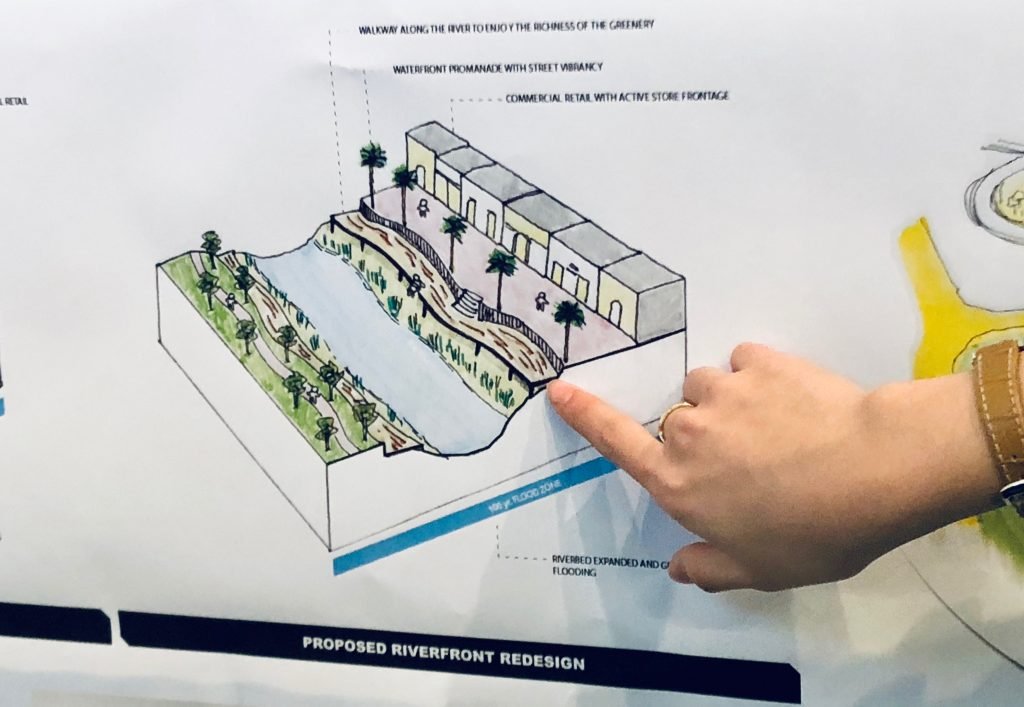

Urban planning students present an intervention project on the Viví River in Utuado, Puerto Rico.

Two of these labs focused on urban planning and landscape architecture projects to improve human settlements near San José Lagoon, and on the resilience plans needed by the municipalities of Utuado and Naguabo. A third study generated recommendations for remodeling housing in the Luis Lloréns Torres residential area, and the fourth lab studied the response of the city of Filadelfia to Puerto Ricans displaced by the hurricane.

For the Luis Lloréns Torres project, the students suggested creating a green area next to the lagoon’s mangrove bed , to be intentionally flooded during storms and reduce flooding in homes; increasing connectivity between nearby residential areas by removing physical barriers such as walls and storm drains; and implementing a water collection and storage system in case of contamination or a water outage.

“We suggest that residents submit their ideas for the redevelopment of the complex because, historically, they haven’t been included in the decision-making process,” said Terence Hogan, one of the students involved in the project.

José Juan Terrasa-Soler, director of Marvel Merchandise and professor of landscape architecture at the Universidad Politécnica, comments on the Luis Lloréns Torres housing project.

The complex is the second- largest public housing development in the United States, with 2,451 family spaces, preceded by the Queensbridge complex in New York City.

Lisa Servon, chair of the University’s Department of Urban and Regional Planning, said this was the first time the design school’s internship was entirely dedicated to Puerto Rico and the Puerto Rican community. In previous years, they have focused on projects located in Guatemala, Mexico, Ecuador, and other cities in the United States.

“These studies try to propose big ideas, and I thought it was important to highlight the consequences of Hurricane Maria, and the entire history of Puerto Rico before that,” he said.

In the study dedicated to evacuees in Philadelphia, the students suggested that local, state, and federal governments create a one-stop shop, both physical and virtual, that could centralize and facilitate access to the necessary assistance and guidance. They also suggested establishing a working group for long-term preparedness for future mass migration events. Currently, there are a number of decentralized government and nonprofit organizations, which complicates the process of applying for social assistance for evacuees.

Other ideas include allocating FEMA funding for temporary housing to an Airbnb-style pilot program , which could offer immediate, short-term housing options in partnership with local landlords; supporting the creation of housing cooperatives; and developing a common remittance account so Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia can directly contribute to development projects on the island.

“We’re working on the basis that any state or city can implement the ideas we’re sharing, since any location could be the next to receive a large group of people due to a natural disaster,” said Ariel Vázquez, an instructor at the lab focused on Puerto Rican evacuees in the city.

One of the challenges the students faced was the existence of multiple sources of data on the number of Puerto Ricans coming to Philadelphia after the 2017 hurricane season.

According to the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency , more than 3,400 people moved to Pennsylvania in June 2018. Of those, more than 2,000 registered through the Philadelphia Disaster Assistance Service Center.

According to Philadelphia Public Schools data for the 2017-2018 school year, 206 displaced students had enrolled as of December 2017. As of January 30, 2018, according to a research paper published by the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, 414 displaced students were enrolled in the system.

José Ríos comments on the projects developed by students to rebuild and prepare the municipality of Utuado for other natural disasters.

José Ríos, president of the Utuado municipal council, said the students’ presentations shed light on resources that local officials had not yet considered.

“These projects give us a glimpse of what we have and, in many cases, what we don’t know we have,” he said. “People outside of Puerto Rico see our value, resources, and potential.”

Published by: Jesenia De Moya Correa

Communities & Engagement Journalist, specialized in health and science reporting for bilingual Latino audiences.

Periodista apasionada por la salud ambiental, las ciencias y las diásporas latinas en el continente americano.

If you’re having problems sharing via email, you might not have email set up for your browser. You may need to create a new email yourself.

Communities & Engagement Journalist, specialized in health and science reporting for bilingual Latino audiences.

Periodista apasionada por la salud ambiental, las ciencias y las diásporas latinas en el continente americano.